Tucked away in my father’s files were some old papers, documents which provided clues about his journey from East Pakistan to India in the early decades of India’s independence. These clues tell a story of displacement, nation-building, and of the shifting meanings of home, identity, and memory. His path, which began in 1936, and spanned more than eight decades, resonates to this day, in what it tells us about the post-colonial experience and the unresolved traumas of forced displacement.

Sometime between 1947 and 1960, my father, a citizen of India, became a refugee, or, in official parlance a “bonafide displaced person”. I am unsure about the exact year because we rarely talked about that time. What we did talk about was his memories of his original home, in what is now Bangladesh. As he got older, these memories grew stronger – and yet more vague. It was only last year, after his demise, that I gained a better understanding of his journey. Tucked away in his desk were some files, the ones he thumbed through again and again. Here, I found some tattered documents, that allowed me to piece together a story of history of displacement and identity.

My father, whom I will refer to as Mr. Biswas, was born in 1936 in the district of Barisal, located in what is now Bangladesh. At the time, Barisal was in British India, and he was a British subject. That changed in August 1947, when Britain finally left India and the country gained independence. This was an event celebrated by many, as this newspaper clipping shows.

Caption: Newspaper headline from August 15, 1947

Source: Deccan Herald

But, what was Mr. Biswas’s national identity at this point? In the chaos of 1947, this remained unclear. British India has been partitioned into two countries, India and Pakistan. Pakistan was to be a Muslim-majority state, a home to Indian Muslims who were apprehensive about their position in a Hindu-majority India. India’s leaders at the time were committed to building a secular and inclusive state; however, the majority of the country was Hindu by religion. For reasons that have been extensively documented, the split was chaotic and violent, displacing, as of 1948, fifteen million people and leaving between one and two million dead. It remains one of the largest mass migration movements the world has ever experienced.

Caption: Map of the Partition of India & Pakistan after August 1947

Source: BBC

The newly carved nation of Pakistan was geographically an oddity. Its two sections, East and West Pakistan, were split by almost 1500kms of Indian territory. Even though my father’s family was Hindu, they stayed in Barisal, in what had become the Muslim-majority East Pakistan. The reasons for the decision to stay was not clear. When I would ask my father why they did not immediately move to India, he would say “Bangladesh was our home, we had a little bit of land there, we are Bengalis, you know.”

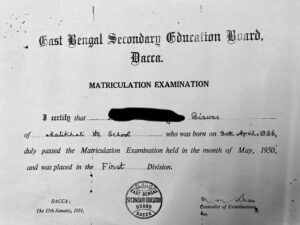

And so, in 1947, amid the joys and the tragedies of Independence and Partition, my father, like many other Bengali Hindus, found himself living and studying in East Pakistan. In 1950, at the age of 14, he completed his secondary schooling in the city of Dacca (now Dhaka), the capital of East Pakistan.

Caption: Certificate of school completion, Dacca, 1950

Source: Author photo

During this time, amid rising tensions between East and West Pakistan, things were getting difficult for Bengalis. Shortly after completing his school education, my father moved to India. His port of entry into the country was the province of West Bengal, which borders East Pakistan, and shares linguistic and cultural affinity with the people of that region of Pakistan. There, in 1961, at the age of 25, my father was registered as a citizen of India. He was born at home; and, other than the school certificate from East Pakistan, this was his first ‘official paper’.

Caption: Certificate of citizenship registration, Barasat, 1961

Source: Author photo

When I found this document, I looked at it a long time: this is the only photograph I have seen of my father as young man. Photography was expensive, certainly too expensive for someone who was living on scraps in a new city.

That same year, Mr. Biswas went to another office to obtain a different certificate. This one confirmed his status as a person belonging to a Scheduled Caste, that is, a lower-caste or Dalit community. The Government of India, in recognition of the historical oppression and marginalization that Dalits have experienced, had announced a series of remedial provisions in education, employment and housing. This document was the proof needed to access these programs.

Caption: Certificate of caste, Alipore, 1961

Source: Author photo

When I look at these papers, I visualize my father. I see him, arriving in the city of Calcutta, a large metropolitan city teeming with long-term residents, migrants looking for jobs, and millions of refugees from East Pakistan. Calcutta (now called Kolkata) was the capital of a state, West Bengal, that was reeling from the violence and mass migration that had accompanied Partition in 1947. As Siddharth Mukherjee writes in his acclaimed book, Gene, this was a time when the city itself “was losing sanity—its nerves fraying, its love depleted, its patience spent”. And India was still trying to find its ground as an independent, post-colonial country, with few resources at its disposal.

Amidst this chaos, Mr. Biswas had no assets to his name and very little money. He was the oldest son of a family that has lost its land in East Pakistan and he was, therefore, the principal breadwinner. While India was always my father’s country; this part of India, the new India, was also a foreign country, different from his home in rural East Bengal. I imagine him going to an office in Barasat, trying to register himself as an Indian citizen. I see him standing in line, jostling with the many others who are doing the same. As anyone who has been to an immigration office anywhere in the world, this process, the one that leads to the all-important paper ascertaining one’s legality, is laborious and stressful. By its very nature, it strips you of your confidence and sense of self. Much depends on the mood of the officer handling one’s ‘case’. It also requires money – money to get documents notarized, to get a photo taken, to make copies, and, in some instances, to offer bribes.

After getting his citizenship paper in the locality of Barasat, which surely took hours, if not days, Mr. Biswas must then go to Alipore to get his caste certificate. Alipore is 45 kms from Barasat. At a minimum, he would have had to take two buses, or perhaps a train and bus, to get to his destination. This too, takes, money and time. And in this office, as well, he must once again make copies, stand in line, provide his details, and hope that his case officer provides the all-important signature. Time, money, luck—all of these are needed and all of these are in short supply.

But there are yet more documents to obtain, more lines to stand in, more evidence to provide, to prove what has already been proven. These are two documents from 1962 and 1963, one attesting that he is a citizen of India and one attesting that he is a “bonafide displaced person”. Note that the office of Refugee Relief and Rehabilitation states that my father, despite his displacement, is not entitled to rehabilitation benefits. Interestingly, Joya Chatterji provides an exhaustive account of the variable ways in which refugee benefits were distributed and withheld in West Bengal. In her book, she notes that “between 1947 and 1967, at least 6 million Hindu refugees from East Bengal crossed into West Bengal: and she documents the ways in which these refugees sought to “find shelter, jobs and security”. My father was just one of these 6 million; yet, his story was repeated, year after year, for those millions.

Caption: Additional papers, Calcutta, 1962-1963

Source: Author photos

At the same time, my father was also trying to get a college degree, obtaining a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Calcutta, eleven years after having completing his secondary education.

Caption: College Graduation Certificate, Calcutta, 1961

Source: Author Photo

My father had a reputation has having been an excellent student. Yet, he did not do well at the University of Calcutta, barely passing his exams. I know this because it has often been mentioned within the family – that he used to be “good at studies”, but that he was “not good in college”. When I would ask him why that was the case, my father would only mumble, “there was lot going on those days, this and that happened”. He never said anything more than that.

Looking at these papers, I now see what the “this and that” was. It was getting papers after papers certified, it was finding ways to make some money, it was about finding his place in a country that had always been his country–but also one that had, literally, moved under his feet.

Eventually, Mr. Biswas got a job with the Government of India and built a comfortable life for himself and his family. Yet, the need for papers continued. In 1979, for example, at the age of 36, he obtained yet another certificate to attest that he was a displaced person.

Caption: Displaced person affidavit, Delhi, 1979

Source: Author Photo

By this time, East Pakistan had ceased to exist, having become Bangladesh. The creation of Bangladesh had been preceded by another massive exodus. Brutal actions by the Pakistan military led 10 million Bengalis to escape to India over a span of nine months. Most of these Bengalis streamed into West Bengal. The Indian government’s responses to this situation, and what it tells us about the evolution of the global refugee regime, is the subject of my recent article in Refugee Survey Quarterly. My father had often expressed great sympathy for these refugees. I wonder if he had seen something of himself in them.

Mr. Biswas’s successful quest for the papers that would attest to his identity as an Indian citizen shows, through an individual case, the relationship between identity documents, citizenship, and state-building in South Asia. Indeed, as Vadha Chhotray and Fiona McConnell argue in an article published in Contemporary South Asia, an examination of such papers “offers a valuable lens onto how migrants, refugees and socio-economically marginal individuals seek to negotiate their relationship with the state”.

In her book Citizenship and Its Discontents, Niraja Gopal Jayal points out that identity documents help construct and support some essential components of citizenship — legality, rights, entitlements, and identity. However, the legality of citizenship intersects with the affective dimension of identity in ways that cannot be easily predicted or understood. As most migrants and refugees know all too well, moving across borders- or having the border itself move- can leave one in a state of confusion. In his later years, and particularly after having retired from his job, my father became more and more nostalgic about his childhood in East Bengal. He came to live almost entirely within his memories, with romanticized notions of the scenery, the food, the water, all the riches that the Bangladesh of his mind offered. He became less and less interested in the city of Kolkata, where he had lived much of his life, and more immersed in the ways that he remembered his “home over there”.

Kolkata is a mere 250 kms from Barisal. Today, several daily buses connect West Bengal and Bangladesh. I think of all the things that those 250 kms have witnessed over the span of just a few decades, the untold millions whose experiences of displacement are just footnotes in the stories about the end of British imperialism and the birth of new nations. I think, as well, of these two gold bangles that my grandmother had given me.

Caption: Gold bangles

Source: Author Photo

She had told me to guard these bangles with care, to never sell them or exchange them for other jewelry. Last year, that I discovered that these were the only things of value, hidden in a pot of rice, that she had brought with her as she walked those 250 kms , from her “home over there” to her “house over here”.

Author information: Bidisha Biswas is Professor of Political Science at the Western Washington University as well as Associate Senior Fellow at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg / Centre for Global Cooperation Research (KHK/GCR21).