If anyone gets numbers, it’s Hong Kong, which just announced a US$8.2 billion surplus. But one statistic just doesn’t make sense: the zero success rate for asylum seekers. To start addressing it, Hong Kong society must come to terms with its refugee past.

Last month, the Hong Kong government confirmed that it had approved five new applications by asylum seekers, the first batch of successful cases under a claims system introduced in March last year. While five cases would sound like a drop in the ocean to most, statistically speaking, they are significant, because they brought the total number of recognitions in the territory to 28. That is, 28 ever since the Torture Convention first came into force in the territory in 1992, out of a total of at least 9,590 determinations.

It does not take much to figure out what that means: a recognition rate of around zero per cent.

Advocates call this a statistic improbability, even impossibility. To be sure, the number does not jive with what we know from global figures. In 2013, 34 per cent of first-instance claims in the European Union received protection, while globally according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the total recognition rate stood at 43 per cent. Meanwhile in China, 50 of 147 applications received some form of protection (See Table 9 in this link).

While China has signed the Refugee Convention and 1967 protocol, the instruments have never been extended to Hong Kong, a special administrative region which has its own government, laws and judiciary. The Hong Kong government’s stance can be summed up in its notice to claimants: “The 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees or its 1967 Protocol has never applied to Hong Kong. The government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region has a long-established firm policy of not granting asylum to or determining the refugee status of anyone.”

Even so, there have been limited avenues to seek protection. For years, a two-path system existed. First, asylum seekers could apply for refugee status with the UNHCR. Second, they could apply with the Hong Kong government for non-refoulement protection under the Torture Convention, which, unlike the refugee instrument, has been extended since 1992 to the territory.

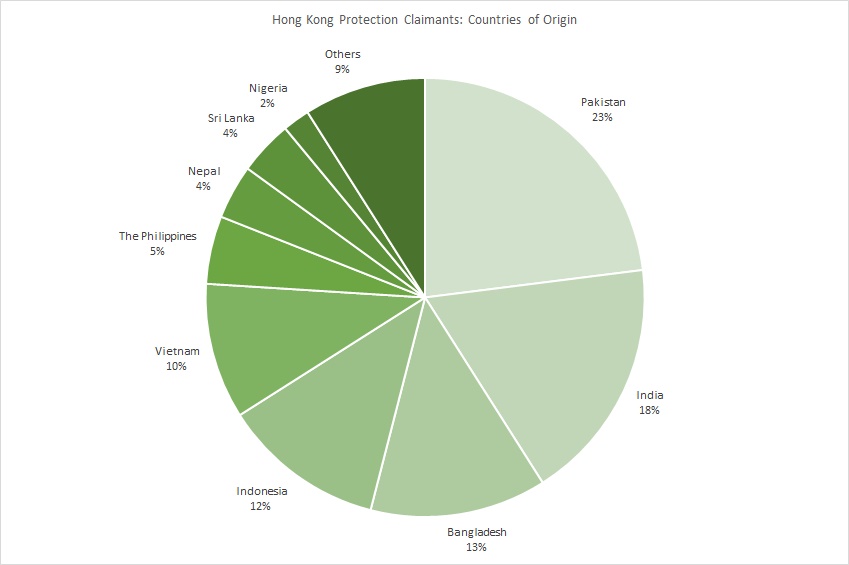

Among the 9,580 applications that were outstanding as of November last year, the top three countries of origin for protection claimants were Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, according to statistics obtained from the Immigration Department by Justice Centre Hong Kong, an NGO supporting forced migrants. By law, they may only apply for non-refoulement protection when they are required to surrender or are already subject to removal.

Source: This image was created based on data provided to Justice Centre Hong Kong by the Hong Kong Immigration Department.

Several landmark judgments have forced the government to make changes. Most recently in March last year, it introduced the unified screening mechanism, which did away with the two-path system. This resulted from two judgments. One ruled that when determining whether to deport someone, the government must screen for cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment at the country of origin. Previously it had done so only for torture. The other ruled that in assessing the risk of persecution before deportation, the government cannot simply rely on the UNHCR’s decision regarding refugee status, but must conduct an assessment itself. As a result, the UNHCR phased out its determination procedure and the two-path system was replaced by the unified screening mechanism.

The new mechanism bears similarities to the torture screening procedure. Once claimants give a written signification of their application, they have 28 days to submit their claim forms and supporting documents. They then attend an interview, after which a written decision is given. If rejected, they can appeal within 14 days to the Torture Claims Appeal Board. They can also file a judicial review at the High Court.

Unlike the old system, which only screened for torture, the new mechanism also assesses for cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment, as well as persecution.

Notably, protection claimants in Hong Kong have access to free legal assistance and representation – a measure which would make it the envy of rights advocates in jurisdictions like Germany and the U.S. If, as studies like the one in Refugee Roulette show, the presence of counsel is the single most important determining factor in whether a claim succeeds, a genuine claimant would theoretically be in a good position to win their case in Hong Kong.

Yet, the substantiation rate has remained near zero.

What does it mean that the Immigration Department of Hong Kong decides against almost all non-refoulement claims? Could it be that the government is correct, that over 99 per cent of the people who come to us are not actually fleeing from danger? Or is it more likely that something is not right in the system?

For many experts in the territory, the answer would be the latter. As Mark Sutherland, a barrister and non-executive director of Vision First, a refugee NGO in Hong Kong, recently told me: “Statistically, it cannot be right that there is a near-zero acceptance rate.”

What are the reasons for this rate? That, Mark Daly, a human rights lawyer who has acted in the majority of the test cases that forced the government to set up the new mechanism and who is a trainer for the profession, recently said to me, “is the sixty-four-dollar question”.

The government has repeatedly denied claims of unfairness, saying claimants have access to free legal assistance, a medical examination, an interview, an appeal mechanism, and other measures. The process, it claims, might be prolonged when the claimants fail to cooperate. “Any purported correlation between the number of substantiated claims and the standard of fairness or effectiveness of the screening procedures has no rational basis,” it said in 2013 in response to criticisms.

A difficulty in explaining the low substantiation rate lies in the lack of transparency. The Immigration Department does not publish statistics of its own volition, preferring to provide answers reactively. Anecdotal evidence from lawyers and NGO workers suggest the low rate lies in inadequate knowledge, training, and strategic planning; a cultural bias; and the pressure to process cases quickly. I would further argue that it lies in racism and a denial of the city’s refugee past generally in society.

Lawyers have often noted the lack of knowledge and expertise displayed by decision makers at the Immigration Department and administrators in the publicly funded legal assistance scheme for claimants. “There remains institutional and cultural bias towards claimants and there needs to be ongoing training of the decision-makers,” Daly said. “There are also legal errors in the decisions and the courts can and have played a role in providing guidance to the decision-makers however the process of challenging decisions by judicial review takes time. Ongoing training is required for both decision-makers and in my view judges involved in this area of the law.” He noted that this area of human rights law was not required study.

Robert Tibbo, a lawyer who represents some claimants, recalled one administrator asked him what a Palestinian was. “A lot of it is lack of education,” he said. The decision makers, Tibbo told me, receive “very, very basic training” on what persecution, torture, and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment and punishment are, but it is “wholly inadequate”. Daly said that equally, further training was necessary for lawyers assisting claimants, adding however that they were “hamstrung” by unrealistically short deadlines for filing submissions and low fees.

The need for speed is also a factor. Sutherland recently noted the department’s practice of trying to process cases quickly with little regard for overall fairness. The time allowed to file the claims and supporting documents, he said, was not enough.

Lawyers like Daly and Tibbo blame a cultural bias at the Immigration Department. Perhaps tellingly, the section responsible for screening the claims has been named the “removal assessment section”, whose tasks also include “formulating and implementing policies in respect of investigation, deportation and removal”.

A lack of strategic planning has meant the government’s claims procedure has been vulnerable to legal challenge, with the result that every time the court rules against it, it has to rehash it again. Justice Centre Hong Kong, an NGO assisting vulnerable forced migrants, suggested in a report last year that the government is only “doing the bare minimum … [and] nothing more” to meet its obligations under the court rulings. Daly added that there were other problems, including the difficulties in obtaining evidence, particularly medical evidence, to support the claims. “All of these factors combined make it an uphill battle to achieve success in the present system,” he said. “That said, we have had a number of the few successes in the system and have no option but to continue to battle to make the system more fair.”

I would further argue that a steadfast resistance against acknowledging Hong Kong’s longstanding history as a de facto receiver of refugees, as well as discrimination – not just in the government but society as a whole – are as important as the factors already mentioned, if not more so, in explaining the low recognition rate.

Discrimination remains a reality. According to the World Values Survey results released in 2013, about 27 per cent of Hongkongers did not wish to live with someone of a different race. This prompted York Chow, chair of the government’s Equal Opportunities Commission, to write a commentary titled “Racist Hong Kong is still a fact” in the SCMP. Racism, Tibbo noted when we spoke recently, is not unique to Hong Kong, but a problem nonetheless, and affects how asylum seekers are treated. “Hong Kong’s majority ethnic Chinese society continues to be intolerant to those who are different.”

Where does it come from? As Charles Sturt University post-doctorate research fellow Francesco Vecchio explains in his book Asylum Seeking and the Global City, a perception of superiority over people of South Asian descent – the background of many of Hong Kong’s asylum seekers – developed after the 1967 anti-colonial riots, when the British government attempted to de-sinicize the territory and a distinction was made between the city’s achievements and the relative poverty of its neighbors (Vecchio 2015: 51).

Hong Kong’s rejection of its past as a land of refugees can be compared to Germany’s denial of its nature as an Einwanderungsland, or land of immigration, for the way it has hampered the development of appropriate policies. As Douglas B. Klusmeyer and Demetrios G. Papademetriou noted in Immigration Policy in the Federal Republic of Germany, the country’s insistence on calling itself “not-an-immigration-land” limited its ability to deal proactively with the challenges that immigration posed (Klusmeyer, Douglas and Papademetriou 229: xxi). In Hong Kong, the wholesale refusal to assess or give refugees status by successive governments has resulted in a haphazard apparatus for screening them and taking care of their most basic needs.

Even a perfunctory glance at history would reveal that Hong Kong has often been a place of refugees, in fact even if governments have refused to acknowledge them in name. The two main groups have been the mainland Chinese and the Vietnamese. Different numbers have been cited regarding the number of people who arrived from mainland China fearing war, persecution, and political turmoil during the Japanese invasion, the civil war, and later the Cultural Revolution. According to Chen Bingan, author of The Great Exodus to Hong Kong who spoke with the South China Morning Post in a 2013 interview, various media outlets and scholars have said 560,000 escaped to Hong Kong from mainland China from 1949 to 1974. However, Chen suggests the real figure is two or three times that.

In 2013 Chinese University of Hong Kong professor Ho Piu-yin estimated that up to 30 per cent of the population between 1961 and 1981 comprised mainlanders who had fled. A mission tried to measure the refugee population in a report submitted to the UNHCR in 1954 which was cited by its head of mission, former International Court of Justice registrar Edvard Hambro in his essay “Chinese Refugees in Hong Kong” in The Phylon Quarterly in 1957. Because of political reasons, those who arrived could not be classified as refugees.

However, the mission surveyed those who claimed a well-founded fear of persecution and due to that fear were unwilling to return to China, and also sought to find out why they had left and the conditions under which they would return. It concluded that up to 12.7 per cent of the population fit the description of a refugee in 1954. (Hambro was likely only referring to the heads of families.) When the heads of families who had arrived pre-war and claimed an unwillingness to return for political reasons were added, along with their family members, the figure totaled 677,000, roughly 30 per cent of the population at the time.

As a result, Hambro asserted that “the colony’s most important function is a haven for Chinese fleeing” and that “for Hong Kong to be flooded with refugees is not novel”. “Nowhere is the refugee problem less dramatized…” (Hambro 1957: 69, 71). His comments were echoed half a century later. As journalist Athena Chiu wrote in Time Out in 2013, Hong Kong has “long had a history of being a safe haven for refugees from all over the world”. However, the refugees were largely forgotten, as Chen told the SCMP in 2013. “Neither the mainland nor Hong Kong governments want to propagandize or memorialize the escapees, because of the associated political taboos.”

China has long denied the idea of a mainland “refugee” in Hong Kong. “The Chinese living in Hong Kong and Macao are by no means ‘refugees’ and the so-called ‘question of Chinese refugees’ simply does not exist,” Beijing said in 1972, according to a daily report from the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (Muntarbhorn 1992: 59). The colonial government’s official policy, Hambro wrote, was not to recognize refugees. The United Kingdom decided not to extend the Refugee Convention to Hong Kong out of fear of opening the floodgates to Chinese immigrants (Whitney 1998: 1).

The stance today against refugees has also stemmed significantly from Hong Kong’s past with Vietnamese boatpeople fleeing the Vietnam War. This experience lasted 25 years and cost the territory HK$1.6 billion. The situation was exacerbated as other countries like the United States which initially had offered to take in the refugees backed down, leaving many stranded in Hong Kong, lawyers for the firm Well, Gotshal & Manges wrote in a brief in the Duke Journal of Comparative and Internatonal Law in 1993 (Burton and Goldstein 1993: 73). The influx of over 200,000 Vietnamese refugees, writes Vecchio in his book, has affected the city’s perception of asylum seekers today. Over time, the Vietnamese came to be seen as “a threat to society and, consequently, were identified as migrants seeking to escape poverty rather than political persecution” (Vecchio 2015: 53).

Until Hong Kong confronts its refugee past and racism, provides better education and training to decision makers and lawyers, and engages in better strategic planning, the zero recognition rate will remain.

Hong Kong scores highly according to many measures: market freedom, trade, good food, an alluring skyline. But when it comes to protecting people fleeing from danger, it continues to get zero marks. As oft noted, including by the authors of Refugee Roulette, the mark of a great nation is how fairly it treats the most vulnerable. Hong Kong has a long way to go before it can turn its improbable statistics into something that makes more sense.

References

Burton, EB & Goldstein, DB 1993, ‘Vietnamese Women and Children Refugees in Hong Kong: An Argument Against Arbitrary Detention’. Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law, vol. 4, no. 1.

Hambro, E 1957, ‘Chinese Refugees in Hong Kong’, The Phylon Quarerly, vol. 18, no. 1.

Immigration Department Hong Kong 2015, Response to Application for Access to Information. Available from: www.justicecentre.org.hk. [January 7, 2015].

Klusmeyer, DB, & Papademetriou, DG 2009, Immigration Policy in the Federal Republic of Germany: Negotiating Membership and Remaking the Nation, Berghahn Books, New York.

Muntarbhorn, V 1992, The Status of Refugees in Asia, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Vecchio, F 2015, Asylum Seeking and the Global City, Routledge, London.

Whitney, KM 1998, ‘There Is No Future For Refugees in Chinese Hong Kong’, Boston College Third World Law Journal, vol. 18, no. 1.