By Alexandra Lestón & Yaatsil Guevara González

For decades, thousands of people from Central America have been forced to leave their homes due to the extreme violence, poverty and marginalization they face in their countries of origin. Mexico has increasingly become a place of refuge for them. In this blog (also published in German and Spanish), we portray diverse testimonies about how Central American refugees are experiencing and surviving the COVID-19 pandemic crisis in Mexican territory.

“… I have this dream of being able to study here, like I did in Honduras… I’ve always wanted to study, to become someone in life, but unfortunately in Honduras I was kicked out of school because of the gangs, because of the Maras… unfortunately Honduras is mostly gangs, there are more gangs than anything else, they’re everywhere.” (Román, May 11th, 2020)

This is Román’s answer to an interview we had via WhatsApp on May 11th 2020. Of course, we anonymized Román’s name so that his as well as all the other names mentioned in the text are fictive. He is a 16-year-old Honduran refugee who has been living in Mexico since July 2019. He’s part of the estimated 500,000 people who cross the southern border of Mexico each year to seek refuge from the ravaged economic systems and extreme social violence that characterize the Central American countries of Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

Román, like many other people from Central America, was forced to leave his home and flee toward Mexico in July of 2019. After an arduous journey, he arrived at a migrant shelter in Tenosique, Tabasco, a border city in Southern Mexico situated only 60km from Guatemala. At the shelter, Román learned about his right to seek refuge in Mexico and began his asylum application with the support of the shelter’s legal team.

Román’s asylum application was approved, and after living for seven months in the shelter he received support from friends who helped him travel to Monterrey – a large, metropolitan city in the Northern state of Nuevo León. In the shelter where Román lived, legal accessory to asylum seekers has increased massively since 2013 – a statistic reflected in nationwide trends. For people like Román, obtaining refugee status has become virtually the only way to safely transit Mexico (even if it takes longer), as well as the most viable option for those looking to “settle” in Mexico and abandon the goal of reaching the United States.

Here, it’s important to situate migrant persons’ increasing interest in seeking asylum in Mexico as a strategic response to the United States’ border externalization policies: policies which have made transiting Mexico without legal status seemingly impossible, and often deadly. Since 2001, the United States has financed Mexican efforts to detain Central American transit migration with a successive series of policies, many of which were adopted under the guise of economic development or national security. Policies like the Southern Plan (2001), Plan Mérida (2008), the Southern Border Plan (2014), and the US-Mexico Joint Declaration (2019) have increasingly securitized and militarized traditional migratory routes, in turn pushing Central American migrants toward clandestine routes often controlled by drug cartels. Along these routes, migrants are vulnerable to assault, kidnapping, sexual violence, and even mass murder, as in the cases of the San Fernando (2010) and Cadereyta (2012) massacres in the states of Tamaulipas and Nuevo León. This trend of policies that force migrant persons to take more dangerous routes, increasing their probability of „failure“ to cross and death, has been conceptualized by some authors as “Funnel Effect”, “geography of deterrence”, or “hybrid collectif”. Although these concepts emerged from empirical studies on the U.S.-Mexican border, more and more they also reflect the conditions in which migrants transit Mexico.

Faced with the structural violence of the United States’ externalization and deterrence policies and the difficulty of transiting Mexico, the men, women, and children forced to flee their homes in Central America have increasingly looked to Mexico for protection: in 2013, 1,296 people began asylum applications in Mexico; in 2019, the total number of applicants was 70,302. That’s an increase of over 5000% in six years. There has not, however, been a proportional increase in federal budget allocation to the Mexican asylum claims system, which is largely dependent on UNHCR financing. Nor has Mexico addressed asylum seekers’ and asylees’ access to basic rights like housing, work, education, or health care. While Mexican law guarantees equal access to rights and public institutions to all persons present in Mexican territory regardless of migratory status or nationality; in practice, institutional collapse, discrimination and anti-immigrant sentiment widely characterize refugee persons’ interactions with all levels of the Mexican State.

And yet all over Mexico, thousands of migrant persons – both with and without refugee status –invent their own strategies for survival and integration on a daily basis. But how are these strategies affected by the COVID-19 pandemic? How do people, who are already under the strain of constant survival challenges, cope with policies of confinement and restraint?

With these questions in mind, we spent the past weeks reaching out remotely to friends and contacts we had met during previous work in migrant shelters. On the phone, in voice notes, through WhatsApp, text messages, and Facebook messenger, they shared their experiences, perspectives, and hopes for a future after confinement with us. We thank them for their trust and collaboration.

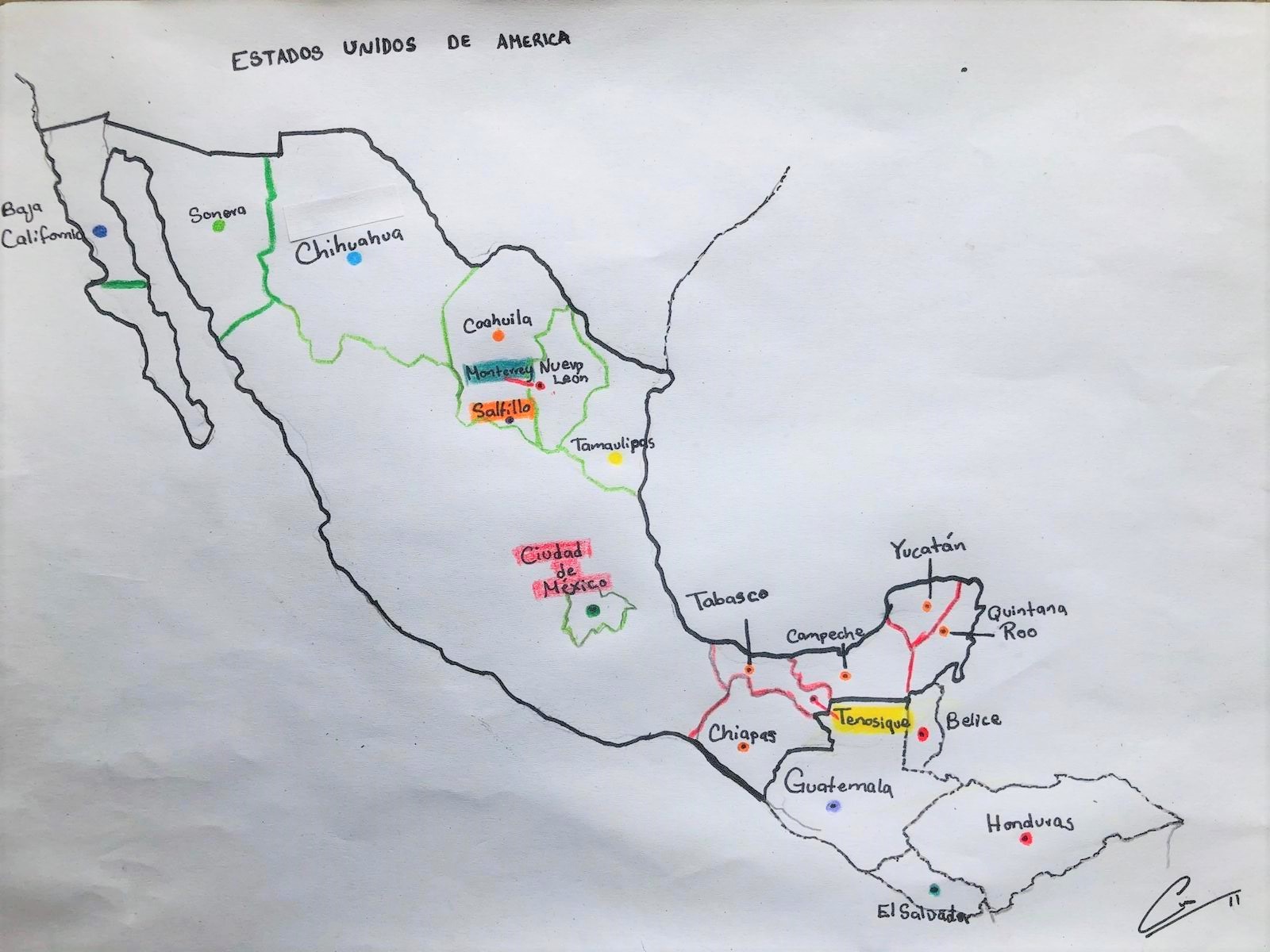

Figure 1. Map of the migratory corridor El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras – Mexico, United States Source and ©: “El chino”, May, 2020

On June 3rd, 2020 there were 97,326 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Mexico, with 10,637 deaths. Apart from overwhelming hospitals, essential workers, and local and global economies, the pandemic has also left thousands of migrant persons throughout Mexico in limbo. The National Migration Institute (INM, by its Spanish abbreviation) has suspended the processing of all visas, residence cards, and other migratory documents, while the Mexican Commission for Refugees (COMAR) had, until May 18, suspended processing of asylum applications. Many migrant shelters and other humanitarian aid organizations have shut down, leaving transit migrants and more vulnerable refugees (such as unaccompanied minors like Román) to fend for themselves. Unemployment and underemployment have also impacted livelihoods in a context marked by discriminatory practice and a large informal labor market (which employs an estimated 57% of Mexico’s workers).

Ema, who is 26 years old, fled her home in El Salvador with her mother and sister in March of 2019. Although they were officially granted refugee status in July 2019, Migration authorities still have not processed their permanent residency:

“I was recognized as a refugee. I’m still living in Mexico City, since we’re waiting for the residence card, because we had a problem during the process and we never got the cards. We were processing them before the virus, but that was put on hold because of the pandemic. If I had to identify myself, I couldn’t, and for any kind of legal documents, like the lease on the house we rent, I can’t use my name…right now it’s under someone else’s name, a friend…but if I want to do things for myself I can’t.” (Ema, May 12, 2020)

Like Ema, Román has also been left in migratory limbo; he was granted refugee status in 2019 but has been unable to finish processing his permanent residency. However, as an unaccompanied minor, the pandemic has also affected his access to vital humanitarian support networks that could help him obtain residency, and be able to return to school:

“Another family that’s from Honduras, my friends, helped me get here [Monterrey]…I’m living with them while the pandemic passes. While COVID-19 passes, so that afterwards I can be in a refugee home, where they can help me study and teach me some kind of trade…I would love, really, I would love to be able to keep studying. I have my school transcripts, I have my papers that show I’m a refugee. I don’t have my residency card but when all of this is over I hope everything gets better and I can get my migration documents in order. I would love, again, I repeat I would love to study, to keep studying, I love information technology especially computation. I don’t have any help from organizations like the UNHCR or COMAR, when I was doing my asylum process they helped me but now I don’t have any support from them.” (Román, May 11, 2020)

Fortunately, Román has received the solidarity of another Honduran refugee family who, at the time of our interview, was still partially employed. However, the economic impact for working adults, especially those who live in Mexico City (the epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak in Mexico), is not negligible. Sebastián, a 36 year-old Salvadoran, has worked since 2017 with a company in Mexico City which offers him trade jobs like “electronic repairs, plumbing, construction…I decided to settle down in Mexico City for work reasons, and I have temporary residency, which was granted to me by the INM” (Sebastián, May 18, 2020). When we asked him how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the migrant community he answered: “Migration has decreased a lot because of the fear of infection, but unemployment has also hit the migrant community.” (Sebastián, May 18, 2020)

Apolonia, who works as a private security guard at shopping malls in Mexico City, was told in February to stay home from work indefinitely. She fled Honduras in 2016 and has lived in Mexico City since 2017, but when the COVID-19 outbreak began in Mexico City she returned to the southern border town of Tenosique, Tabasco, where she currently lives with a friend:

“Would you believe that I’m with a psychosis about this virus, I’m like, my chest hurts, this hurts, that hurts, yeah, I’ve felt a little stuffy, maybe because of the changes in temperature, but I’m like crazy with this, and I was in Mexico City but that’s why I came back [to Tenosique] (laughs).” (Apolonia, May 13, 2020)

In our interview in May, Apolonia described how the pandemic has affected solidarity networks and transit migration along Mexico’s southern border:

[The migrant shelter in Tenosique] “has been closed since March…there’s nobody here, the towns are closed, and the people here actually just want to go back [to Central America]. What they [the authorities] do is that they go and leave people at the ‘El Ceibo’ border, from there the people go to a shelter and from there back to their country, but there’s nothing there, they just waste their time. The other day a woman left the shelter [in Tenosique] saying that she was leaving, that she was going to Monterrey and it’s just that they [the smugglers] trick them, poor lady. Trying to move these days, on these buses, you just get detained [by Migration], everything’s different now but people don’t understand … everything is controlled, all of these towns are basically closed.” (Apolonia, May 13, 2020)

Apolonia’s portrait of migratory movement along Mexico’s southern border is brief but insightful: as in the European context, the confinement provoked by the COVID-19 pandemic has greatly slowed migration streams and complicated processes of international deportation. The United States has suspended immigration court proceedings, and now systematically returns migrants apprehended at the US-Mexico border to Mexico, regardless of nationality. Likewise, Mexican authorities have been signaled by human rights organizations for bussing migrants to the Mexico-Guatemala border and abandoning them there. Transiting through Mexico has also been greatly complicated by the fear of contagion and the number of local checkpoints meant to prevent the transmission of the virus between different cities and towns. Finally, leaving Central America has become virtually impossible due to the authoritarian lockdowns that have closed national borders and greatly restricted citizens’ movements and access to basic necessities inside their countries.

Eunice, who is a 38-year-old migrant who returned from Mexico to Honduras in 2015, shared with us her situation in San Pedro Sula, Honduras:

“And yes, in my country we’re restricted, on weekends everything has to close, everything, everything that’s still operating … supermarkets, the warehouses where they sell groceries, where they sell grains, meat, things like that. The only things that are open are the pharmacies, and the banks. They let you into the supermarket if your ending number [of your personal ID card], matches with the number that’s allowed to go out that day. My daughter’s number ends in 0 and she was allowed to go out today; my number is 6 and I went out on Monday. We pay for somebody to take us to the supermarket or to the bank. And you can be dying of hunger, you can say that your children have nothing [to eat], and that you don’t have anything in your house, and still they won’t let you go out, they won’t let you into the supermarkets in, they stop you if they see you on the street, they stop you, and they take you to jail.” (Eunice, May, 15, 2020)

Undoubtedly, the pandemic has affected all corners of the world, from the bankruptcy of large global companies to the collapse of markets and health systems in some countries. But COVID-19 has also exaggerated the conditions of misery and marginalization in which millions of people live as a result of the inequality produced by our current political-economic system.

In the case of Central American refugee persons living in Mexico, the COVID-19 pandemic has further restricted their already limited access to the labour market and public education system, making their living conditions more precarious. It has also left thousands of people in legal and migratory limbo: from those whose asylum or residency processes have been temporarily suspended, to those who have been abandoned along Mexico’s southern border, to those whose transit has been stalled. In such a trying context, however, it is important to highlight the importance of solidarity networks that migrants weave during transit or (temporary) settlement in Mexico. The Honduran family Román met along the way has temporarily become his own; in the case of Apolonia, old friendships allowed her to escape the pandemic’s epicenter in Mexico City. Ema, who was unable to process her Mexican residency before the pandemic, found a friend willing to sign her apartment lease, thus ensuring that she and her family would have a safe place to ride out the quarantine. In the total absence of State support, local NGOs and faith-based organizations have historically provided critical survival assistance to migrant persons. However, as the COVID-19 pandemic has crippled the operability of the “rescue industry” in Mexico, the solidarity ties migrant persons build over their biographical trajectories emerge as mechanisms of resistance, strategic survival and mutual support. These mechanisms permit, moreover, the persistence of hope in even desolate circumstances:

“Well, I hope, God willing, that when this pandemic is over there are blessings, there is prosperity. Especially for my friends, for family. Maybe after this, well, we are going to rise up. With effort and work, each one of us, well, I think we are going to get ahead.” (Alexander, May 13, 2020)

Figure 2. Photo of food distributed by the Honduran government to families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Source and ©: Eunice, May, 2020. San Pedro Sula, Honduras

This blog post was also published in German and Spanish. Many thanks to Aniela Jesse, student assistant at the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies (IMIS) at the University of Osnabrück, Germany, for the German translation. The authors were responsible for the Spanish and English texts.

Remarks:

*We draw on the term “refugee” in order to highlight the forced nature of migration streams out of Central America. Even if Central American migrants are not recognized as “refugee” before the Mexican State, we understand that all migrant persons coming from these countries have been “expelled” (by conflict, violence or extreme poverty) and as such are deserving of protection.